A practice-oriented reflection on designing for difference in learning contexts

Inclusion is often spoken about as if it has a single, shared meaning. In learning design and education, it is frequently framed as a goal, a value, or a policy requirement.

In practice, inclusion is far more contextual and human.

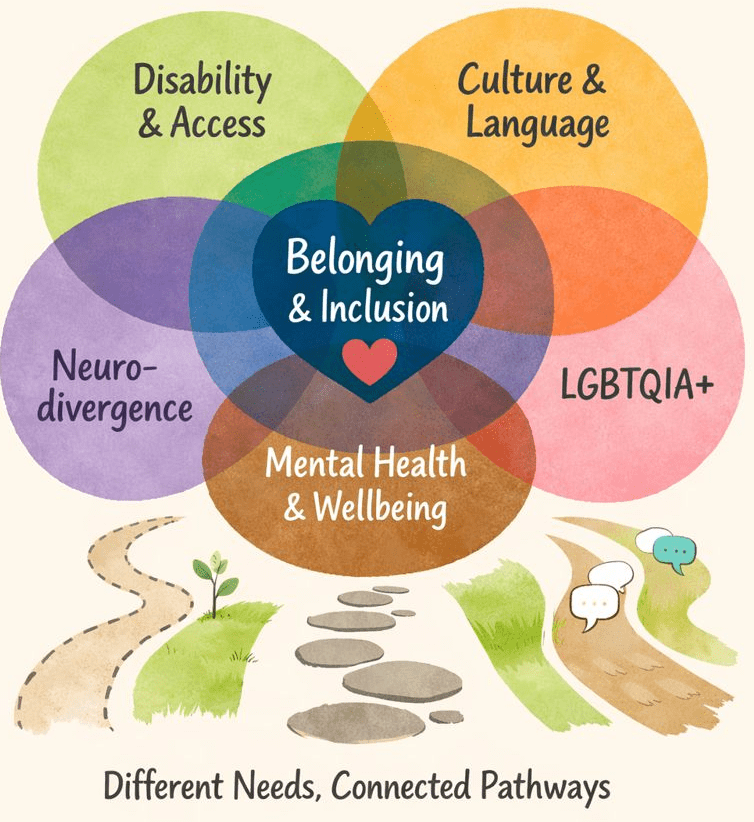

What inclusion looks like, feels like, and requires shifts depending on who we are designing for, what barriers exist, and how learning environments respond to difference. Treating inclusion as one-size-fits-all can unintentionally ignore complexity and hide the very needs we aim to support.

This reflection explores how inclusion is understood across different contexts in education and learning design, and what this means for practice.

Initial questions to hold in mind

As you read, you may like to hold these questions in mind:

- Who is inclusion designed for in my learning context?

- Whose needs are made visible, and whose are assumed?

- How do learning environments respond to difference, uncertainty, and vulnerability?

- Where might well-intentioned design decisions unintentionally exclude?

These questions are not intended to be answered quickly, but to guide reflection throughout.

Inclusion as a contextual concept

Across education literature, inclusion is increasingly understood relational and systemic, rather than individual. It is shaped not only by learner characteristics, but by curriculum design, assessment practices, institutional structures, language, and power.

Inclusive practice, therefore, is not about fitting learners into existing systems. It is about examining how systems are designed, who they privilege, and where barriers are created.

From a learning design perspective, this shifts inclusion beyond accommodation to anticipation.

Designing for different inclusion contexts in education

Learners with Disabilities/ Access Needs

In educational settings, learners with disability often encounter barriers that are structural rather than personal. These include inaccessible digital platforms, rigid assessment formats, unclear instructions, and environments designed for a narrow range of learners.

Inclusive learning design responds by anticipating access needs from the outset. Frameworks such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and accessibility standards like WCAG support this approach by encouraging flexibility, clarity, and multiple means of engagement and representation.

The responsibility shifts from learners requesting adjustments to designers and educators designing access into the learning experience itself.

Neurodivergent Learners

Neurodivergent learners may experience exclusion through hidden expectations, sensory overload, ambiguous instructions, and narrow definitions of participation or success.

Designing inclusively for neurodivergence often involves:

- making expectations explicit

- offering choice in how learning is engaged with and demonstrated

- reducing unnecessary cognitive load

- valuing different ways of thinking and processing

Rather than treating difference as a deficit, inclusive learning design recognises variability as a normal and valuable aspect of learning.

Learners with Psychosocial Disabilities/ Mental Health Challenges

Learners experiencing mental health challenges may encounter changing levels of capacity, reduced concentration, anxiety, or difficulty engaging with high-pressure or inflexible learning environments.

Inclusive practice in this context prioritises psychological safety, predictability, and flexibility. Clear structure, compassionate communication, and options for pacing and participation can significantly reduce unnecessary stress.

Designing for wellbeing does not lower expectations. It removes avoidable barriers so learners are better able to engage and persist.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Learners

Inclusion for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander learners must be grounded in respect for culture, Country, and knowledge systems. Western education systems have historically marginalised Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and learning.

Inclusive learning design in this context emphasises:

- strengths-based perspectives

- relational learning

- community and connection

- respect for cultural protocols

Approaches such as Aboriginal pedagogies and learning from Country remind educators and designers that inclusion is not about adding culture into existing structures, but about re-examining how learning environments are framed and whose knowledge is prioritised.

LGBTQIA+ Learners

For LGBTQIA+ learners, inclusion is closely tied to safety, visibility, and language. The use of language, in particular, in learning environments can create subtle but persistent exclusion.

Inclusive learning design attends to:

- inclusive and affirming language

- visible signals of safety and respect

- policies and practices that protect dignity

- learning spaces where learners are not required to explain or defend their identities

Design choices communicate powerful messages about who belongs and who is expected to adapt.

Intersectionality: why one-size-fits-all inclusion fails

Learners do not belong to a single category. Identities intersect, and barriers compound.

A learner may be neurodivergent, Aboriginal, living with disability, navigating mental health challenges, and identifying as LGBTQIA+. Inclusive learning design must anticipate this complexity rather than segmenting learners into neat groups.

This is where one-size-fits-all approaches fall short. Designing for intersectionality requires flexibility, humility, and ongoing reflection.

What this means for learning design practice

From a learning design perspective, inclusion is most effective when it is anticipatory (thinking about current and future needs) rather than reactive (changing what was already done to fit current learners).

This involves:

- designing with learner variability in mind

- embedding flexibility and choice

- prioritising clarity and accessibility

- recognising the relationship between inclusion, wellbeing, and engagement

Frameworks such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) support this work, but they are tools rather than solutions. Inclusive design is ultimately an ethical stance as much as a technical one.

A closing reflection

Inclusion is not about doing everything for everyone. It is about designing learning environments with greater awareness of who we are designing for and who may be unintentionally excluded.

When inclusion is treated as contextual, relational, and ongoing, learning environments become more humane, responsive, and effective for all.

Reflection prompts

- Who is inclusion currently designed for in your learning context?

- Whose needs are assumed rather than explicitly considered?

- Where might flexibility, clarity, or choice reduce unnecessary barriers?

- How do your learning designs communicate safety, respect, and belonging?

- What would shift if inclusion was treated as a design responsibility rather than an individual adjustment?

Starting points for further reading

- 8 Ways of Aboriginal Learning

- Positive Partnerships (Australian Government)

- Australian Clearinghouse on Disability and Inclusive Education

- Australian Human Rights Commission – LGBTQI+ inclusion

- CAST – Universal Design for Learning

- W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)